The Sistine Chapel was much in the news recently as the Papal Conclave gathered to choose a new pope. The choice of Leo XIV came quickly but, in the run-up to the appearance of the white smoke and cries of “Habemus papam!”, there were many news reports about the site of the conclave. Rather than its usual tourist mobs, the Sistine Chapel for a few days in early May returned again to a purpose closer to its original, one summarized by His Holiness John Paul II in 1994 on the occasion of the unveiling of the latest fresco restoration: “[T]he Sistine Chapel became once again before the whole Catholic Community the place of the action of the Holy Spirit that nominates the Bishops in the Church, and nominates especially he who must be the Bishop of Rome and the Successor of Peter.”

I have been fortunate enough to see the Sistine Chapel and it is breathtaking, overwhelming really. The profusion of figures on the ceiling and in The Last Judgment attest not only to the artistry of Michelangelo but also to the grandiosity of art as it was conceived during the Renaissance. Sure, there are other monumental works of art. Falconet’s eighteenth-century statue of Peter the Great atop a monster boulder of granite? Impressive, without a doubt. Christo’s 1995 wrapping of the Reichstag? Spectacular, mainly for the scale of the undertaking. (Years of planning, 90 climbers, 120 installation workers, 100,000 square meters of fabric, and ten miles of rope culminated in an artwork that lasted fourteen days.) None can compare to the Sistine Chapel.

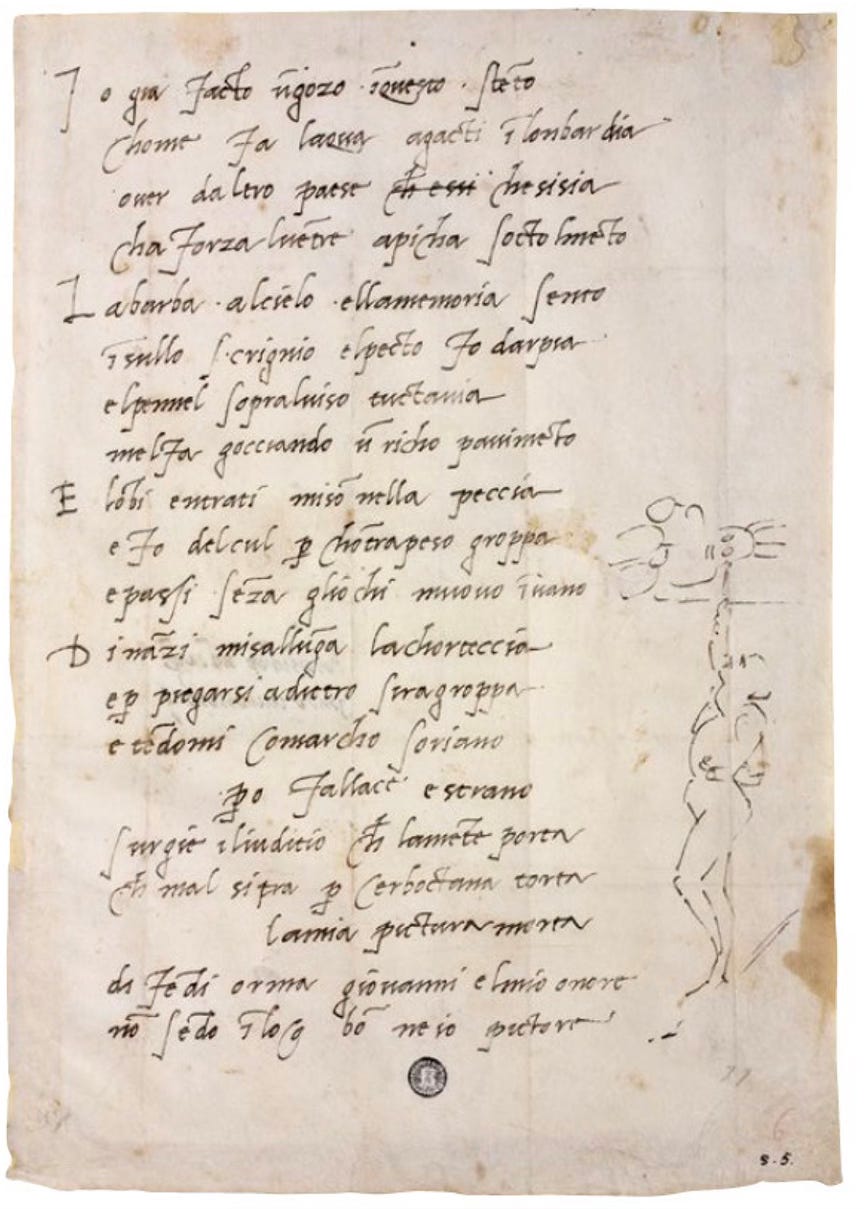

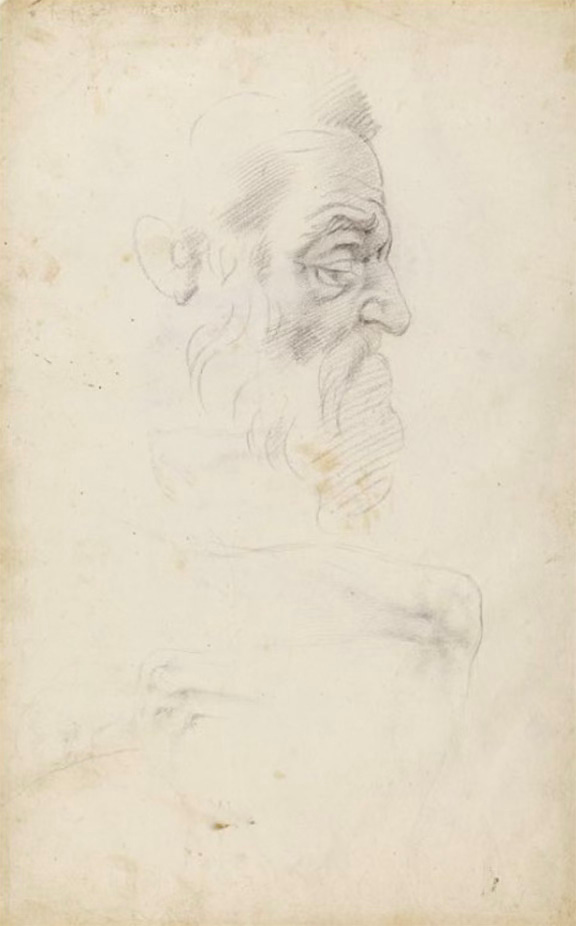

The research exhibition Michelangelo: The Genesis of the Sistine (through June 1) at the Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, focused on the artist’s preparatory work from the time of his commission from Pope Julius II to its completion. (Michelangelo created the frescoes for the Sistine Chapel ceiling from 1508–1512 and The Last Judgment from 1536–1541.) The curator, Adriano Marinazzo of the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, spent fifteen years studying Michelangelo’s work and advances new theories on the artist’s concepts and practices. The bulk of the exhibit consisted of 24 rare drawings by Michelangelo, including a memo about expenses, autograph sonnets with marginalia drawings, and preparatory drawings, some miniature masterpieces, some quick sketches. In addition, other items such coins, a beautiful 1522 Bellini-esque portrait of Michelangelo by Giuliano Bugiardini, and a remarkable set of ten engravings of The Last Judgment by Giorgio Ghisi provided additional context.

Engravings being a favorite of mine, I examined Ghisi’s prints at length. Ghisi divided the huge fresco into ten engravings which he helpfully lettered A through L; a life-sized reproduction shows the pieces assembled into the whole. Ghisi is said to have copied The Last Judgment during a visit to Rome in the late 1540s when everyone was talking about the newly-finished Sistine Chapel. Ghisi, and many other engravers, created widespread interest in Michelangelo’s work through prints which were reproduced and viewed all over Europe. Artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari in his influential Lives of the Artists criticized this proliferation of prints, writing that it was due to “the avarice of the printers [who were] eager more for gain than for honor.” He clearly would have had no patience for the age of mass media.

At the press preview for the exhibition, we were treated to a private tour led by Marinazzo who observed that the Sistine Chapel as we know it almost didn’t happen because Michelangelo insisted that painting was not his art. Michelangelo considered himself a sculptor and urged Pope Julius II to entrust the commission to someone else, a proven painter such as Raphael. While there is no doubt that a Sistine Chapel decorated by Raphael would have been extraordinary, Michelangelo with his sculptor’s approach gives the project a completely different feel, one more masculine and formidable.

Before he could even start, there was the matter of the existing decorative treatment, one we see in a nineteenth-century engraving imaging how the room looked when Michelangelo set to work. (Very plain with a ceiling of what looks like concentric circles of stars.) He first had to devise a scheme that reconciled a sequence of sections in different shapes: twenty-six half-moon lunettes, twelve triangular sails, and nine ceiling panels. Although the setting would seem to dictate a Biblical narrative, Michelangelo decided on a hierarchy of figures including generations of Christ’s ancestors for the sails and lunettes and chronological scenes from Genesis for the ceiling panels. (This site has a clear explanation of the architectural elements and the iconography of the paintings.)

To handle the physical constraints of the space—a barrel vaulted ceiling running the length of a relatively narrow room—Michelangelo imposed a painted architecture concept that resulted in an unprecedented sense of wholeness. “Michelangelo abandons the idea of mere geometric containers,” notes Marinazzo, “and develops a painted structure that simulates real architecture, creating the illusion of three-dimensional architectural elements that gives a sense of depth and cohesion to the ceiling as a whole.” Marinazzo further speculates that the architectural elements took precedence in Michelangelo’s mind because he had been interrupted in another commission heavy on classical features, the tomb of Julius II, one for which the artist had high ambitions. “The tomb,” Marinazzo says, “can be seen as a fundamental element in the conception of the frescoes.” The exhibit underscored this comparison with a wall-sized reproduction of one of Michelangelo’s sketches of the ceiling geometry superimposed on the finished work.

The Last Judgment painted on the Chapel’s rear altar wall closed two windows on that wall and led to the destruction of previous fifteenth-century frescoes. In order to accommodate his plan for this next stage, Michelangelo had to paint over two lunettes, an intervention detectable in the image below. The Last Judgment with its towering figure of a pitiless Christ and a multitude of figures, some agonizing over their descent into Hell, others hurrying toward salvation, centers on the theme of “the physicality of the flesh, the body, and the lacerations of the soul,” writes Marinazzo. Famously, one of these figures, a muscular St. Bartholomew holds his own flayed skin in which the artist depicted his own face. Marinazzo also notes that Michelangelo, never troubled by humility, asserted “I was put here by God to paint the Sistine Chapel.”

The installation of this exhibition is also worth a quick mention. The rooms dedicated to the ceiling frescoes are painted a rich sky blue while the rooms for The Last Judgment are saturated red. The sketches are beautifully framed and wall plaques blessedly free from curatorial editorializing. I was also struck by the quality of the huge wall reproductions of some of the most recognizable scenes such as The Creation of Adam. Marinazzo explained that these came from the Vatican which, in honor of the 550th anniversary of the artist’s birth, provided their very highest resolution photography for the exhibition. I will never again be able to stand this close to the finger of God reaching out to that of Adam. From this angle, I could also consider Marinazzo’s theory that Michelangelo used himself as a model for God. (Very probable.)

In fact, Marinazzo’s presence added much to the exhibition not to mention his contributions, along with those of other scholars, to the show’s handsome catalogue. His warmth and sense of humor brought back to earth a subject that can seem distant and academic. Perhaps the funniest moment came when the native Italian joked that if he ever slips and says “Michael-angelo” instead of “Mikkel-angelo,” he should be put out to pasture.