Her 2019 New York Times obituary described Mavis Pusey as an “under-the-radar abstract artist.” While she may have been less well known than contemporary abstractionists such as Frank Stella or Ellsworth Kelly, the field was crowded in the 1960s and 1970s with, yes, mainly with white, male artists whose often strident works garnered most of the critical attention. The fact that Pusey was a black woman creating abstract art that also suggested narrative themes was most unorthodox at the time.

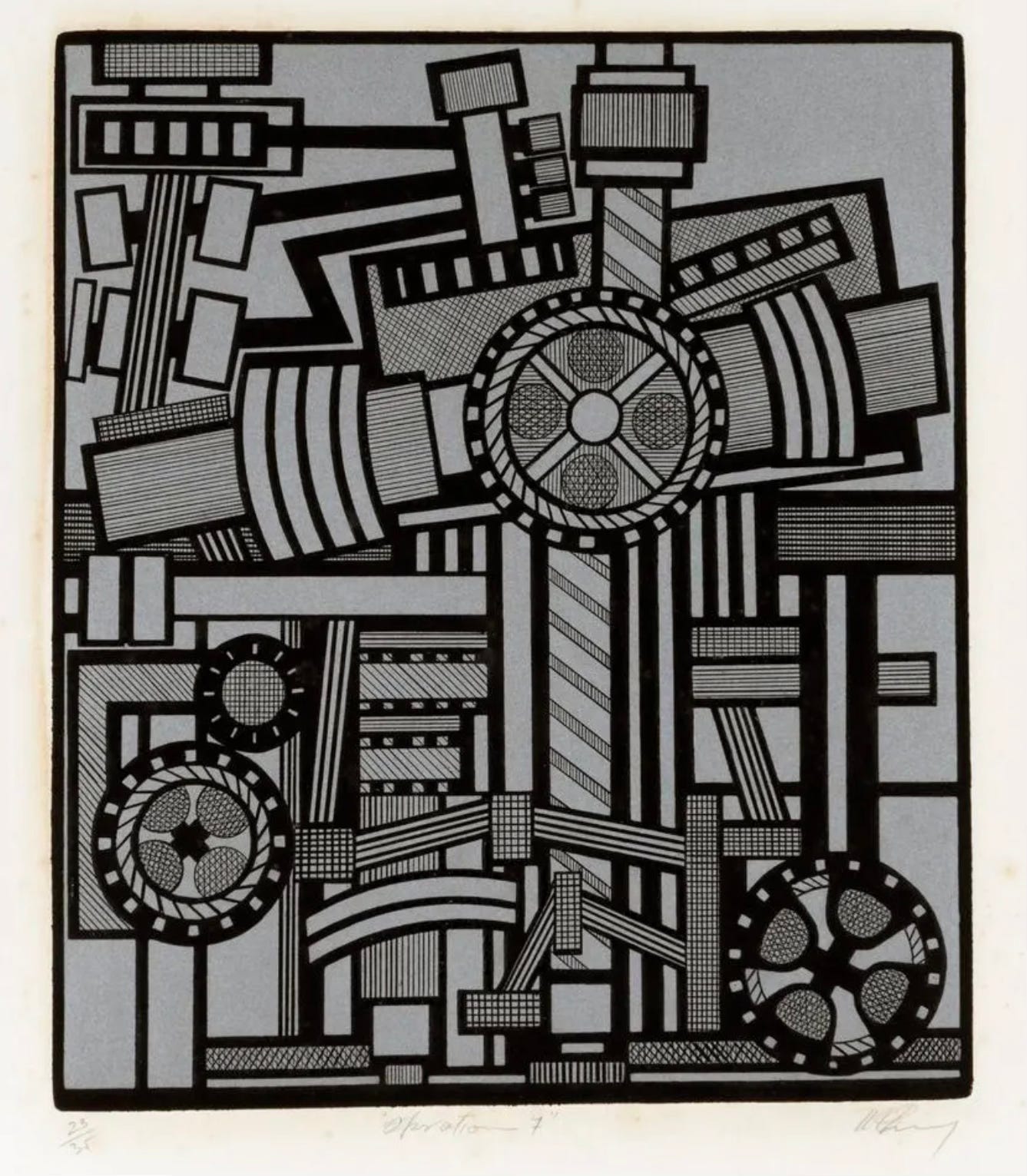

Where artists such as Stella or Kelly produced enigmatic explorations of pure, saturated color, works designed to untether perception from the influence of narrative or representation, Pusey documented everyday life in 1970s New York when so much of the city was being demolished and rebuilt. Her street-level views of broken sidewalks, crumbling walls, shutters, bricks, loose boards, and other debris bring lofty notions about urban renewal back down to earth. She seemed entirely comfortable with the idea of allying abstraction with representation rather than putting theory in the foreground as did her contemporaries. Industrial landscapes, a thicket of electrical wires, or the innards of machinery also inspired her, as in the etching Operation 7, a work that is muscular and dynamic yet intimate in its close-up view of complex parts.

Born in Jamaica in 1928, Pusey learned to sew and worked in a garment factory before she moved to New York at age 18. She was working in a bridal gown boutique when she wandered by mistake into an art class taught by Will Barnet, intrigued but uncertain. When her visa expired, Pusey traveled to London and Paris where she studied art; she eventually returned to New York and her work appeared to much acclaim in the 1970 Whitney show.

Pusey practiced what is known as hard-edged abstraction, a style in which geometry and flat colors supersede painterly concerns with impulse and unpredictability. When it was shown at the Whitney, Dejygea packed a punch, not least because it was a bold and assertive painting by a black, female artist. (The confidence of its composition would also seem to demonstrate how Pusey carried over her mastery of patterns and garment assembly to painting.) Critics seemed baffled that Pusey followed a different track, one that didn’t include art with a predictable, identity-drive narrative.

Big Music

Hard-edge abstraction is founded on strong geometry, and its exemplars are artists of compulsive organization, deep deliberation, and considerable technical expertise. Not to take anything away from what might be called anarchic abstraction —Jackson Pollock’s splatter paintings, for example—but the hard-edged artists were looking to evoke a different kind of response in the interaction of shapes and colors. Russo-French artist Serge Poliakoff worked exclusively in abstraction—some hard-edged, some more akin to color field—and many of his composition were built on a cruciform foundation overlaid with irregular geometric shapes. The drawing below illustrates this idea which is stronger is some of his paintings than in others. Poliakoff’s Russian Orthodox upbringing is often cited as contributing to his love of bold shapes rendered in high-keyed, flat color. Poliakoff said “the picture should bespeak the love of God, even if you don’t believe in God…if you want to get the big music in.” The geometry is there but the irregular contours suggest a different rhythm and expressiveness than Pusey, Ellsworth Kelly, or Frank Stella.

Opposing #15 by Frederick Hammersley is hard-edged abstraction at its purest. The ideas underpinning this exhilarating work are rock solid: perfect color theory pairings (black/white, red/green, blue/yellow) and platonic solids (square, sphere, rectangle/square) that anchor the picture without making it stolid. Hammersley creates an agreeable tension by turning the triangle upside down at the top and placing the unsteady circle at the bottom. He ratchets up the energy with his color selection: The red arrests the eye and everything else expands from there.

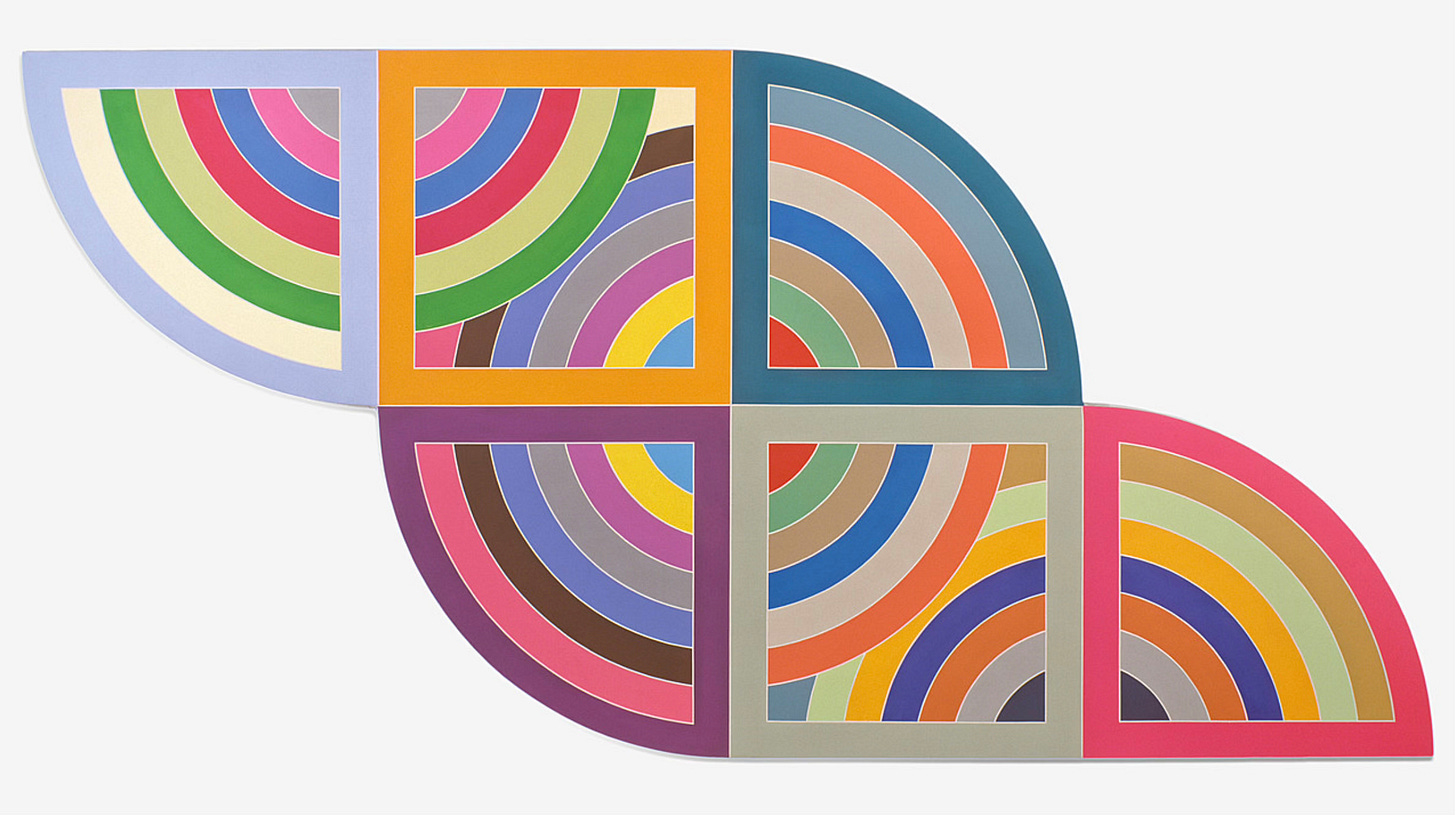

Frank Stella was such a prolific artist that no one label summarizes his long and varied career. His Protractor series, inspired by Islamic art, used a rainbow palette and semi-circular shapes to create mesmerizing works that reconcile abstraction and decorative patterns. The Protractor works, conceived with that most elementary of drawing tools, are monumental in size adding an architectural aspect to these paintings—the two dimensional becomes three. Harran II has a typically playful feel. Stella initiates a number of lines, angles, and curves—you can sense him flourishing his protractor—but never completes any one of them. The whole is lifted into weightlessness by bright acrylics and a nonrectilinear frame.

Serge Poliakoff once said, as if in answer to those baffled by abstract art, “Some may say there is nothing to see in abstract painting. If it was for me, I could live three lives and still would not have told everything I see.”

Coda: What are artists for?

A colleague who was kind enough to read my last two posts on “What are artists for?” reminded me of Susan Sontag’s influential 1965 essay “On style,” in which the novelist and literary critic takes up the vexed question of style and content. Sontag observes that artists with an especially idiosyncratic style (Picasso’s cubism, Barbara Kruger’s sloganeering, Parmigianino’s mannerism) seem “to be preoccupied with stylistic questions and indeed to place the accent less on what they are saying than the manner of saying it.” The way in which an artist expresses an idea is bound to lead to an aesthetic response. For example, even though I respect Wayne Thiebaud’s candy-colored still lifes that gently skewer mass consumerism and the ferocious exploration of trauma in the work of Chaïm Soutine, I can’t admit to a strong affinity for either. (No doubt due to my own narrow tastes.) On the other hand, Egon Schiele’s work can be very difficult to look at but I find his fearlessness thrilling and his expressionistic verve matchless.

Sontag has this to say about the “aesthetic response” to art:

In the strictest sense, all the contents of consciousness are ineffable. Even the simplest sensation is, in its totality, indescribable. Every work of art, therefore, needs to be understood not only as something rendered, but also as a certain handling of the ineffable in the greatest art, one is always aware of things that cannot be said (rules of “decorum”), of the contradiction between expression and the presence of the inexpressible. Stylistic devices are also techniques of avoidance. The most potent elements in a work of art are, often, its silence.

What I like about this is the proposition that even though we look to art for beauty, truth, morality, or authority, its most powerful statement is that which cannot be expressed. Stylistically, art appears to have a lot to say, to be quite vocal in terms of color, line, technique, imagery. Yet, art demurs, it offers silence where we think we see (hear) clamorous expressions of style.